Reading Comprehension Strategies: Skimming, Scanning, and Inference for Better Understanding

Oct, 18 2025

Oct, 18 2025

Most people think reading faster means reading every word. That’s not true. If you’re learning a new language or trying to get through dense textbooks, reading every word will slow you down and drain your energy. The real skill isn’t reading everything-it’s knowing what to skip, where to look, and how to fill in the gaps. That’s where skimming, scanning, and inference come in. These aren’t tricks. They’re proven strategies used by native speakers, college students, and professionals who need to understand more with less effort.

What Is Skimming, and When Do You Use It?

Skimming is reading quickly to get the big picture. You’re not looking for details. You’re looking for the main idea. Think of it like flying over a city from a helicopter-you see the neighborhoods, major roads, and landmarks, but not every house or car.

Use skimming when you’re deciding if a text is worth your time. Maybe you’re scrolling through a research paper before class. Or you’re checking an email from your professor. Or you’re flipping through a textbook chapter before a test. Skimming tells you: Is this relevant? Is this too hard? Should I read this slowly later?

Here’s how to skim effectively:

- Read the title and subtitle first-they often state the main point.

- Look at the first and last sentences of each paragraph. Writers usually put the key idea there.

- Notice bolded words, headings, and bullet points. They’re there to guide you.

- Ignore examples, long descriptions, and data unless they jump out as important.

Try this with a news article. Skim it in 30 seconds. Then ask yourself: What’s the main event? Who’s involved? What’s the outcome? If you can answer those, you’ve skimmed well. You don’t need to know the color of the mayor’s tie to understand the policy change.

Scanning Is Your Search Engine for Text

Scanning is what you do when you know exactly what you’re looking for. You’re not reading for meaning-you’re reading for a name, a number, a date, or a keyword. It’s like using Ctrl+F on a webpage, but with your eyes.

Use scanning when you need a specific piece of information. Maybe you’re looking for the due date on an assignment. Or you need the population of Tokyo in a geography report. Or you’re checking a recipe for how much salt to add.

Here’s how to scan fast:

- Know what you’re looking for before you start. Write it down if you need to.

- Let your eyes move quickly across the page. Don’t stop on every word.

- Focus on keywords, numbers, and capitalized words.

- Use your finger or a pen to guide your eyes-it helps your brain stay on track.

One student I worked with was preparing for the TOEFL. She’d get stuck on reading passages because she tried to understand every sentence. After learning to scan, she cut her reading time in half. She’d scan for the question keywords-like “year,” “location,” or “reason”-and find the answer in under 10 seconds. She went from barely finishing the test to finishing with 15 minutes to spare.

Inference Is the Secret Skill Most Learners Miss

Inference is reading between the lines. It’s when you use clues in the text to figure out what’s not directly said. Native speakers do this without thinking. Language learners often miss it because they wait for everything to be spelled out.

Here’s an example:

“Maria closed the door quietly, grabbed her coat, and walked out without saying goodbye.”

Nothing here says Maria is angry. But you infer it. Why? Because people don’t usually close doors quietly and leave without saying goodbye when they’re happy. You’re using context, tone, and behavior to read the hidden meaning.

Inference is critical in academic reading, literature, and real-life conversations. You’ll see it on tests as questions like:

- What does the author imply?

- How does the character feel?

- What can you conclude about the situation?

To get better at inference:

- Ask yourself: What’s not said but seems obvious?

- Look for emotional words-“frustrated,” “hesitated,” “laughed nervously.”

- Pay attention to contrasts: “She said she was fine, but her hands were shaking.”

- Use your real-life experience. If you’ve ever been in a similar situation, what did you feel?

One common mistake is assuming inference means guessing randomly. It’s not. It’s logic based on evidence. If the text says, “The lights went out, and the crowd screamed,” you don’t infer it was a birthday party. You infer something scary happened. The clues are there.

How These Three Skills Work Together

Skimming, scanning, and inference aren’t separate tricks. They’re parts of one system. Think of them like a toolkit:

- Start with skimming to decide if the text matters.

- Use scanning to find the exact details you need.

- Apply inference to understand what’s behind the words.

Here’s a real example from a college biology textbook:

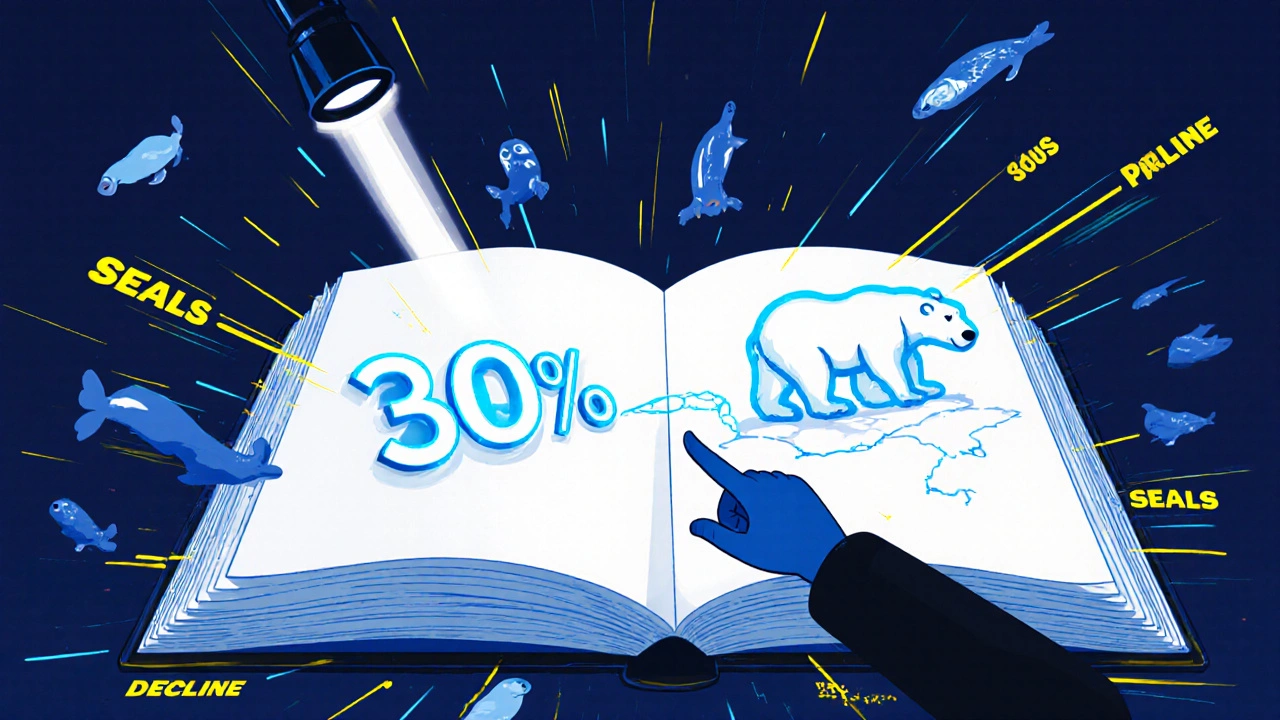

You’re reading a section on climate change. The title says “Impact on Arctic Ecosystems.” You skim it quickly-you see graphs, mention of polar bears, melting ice, and a paragraph on food chains. You decide it’s important. Then you scan for “polar bear population change since 2010.” You find the number: 30% decline. Now you infer: If the ice melts, seals (their main food) disappear, so polar bears starve. You didn’t see that exact sentence, but you connected the dots.

That’s how experts read. They don’t memorize every fact. They know how to find what matters and understand what’s implied.

Common Mistakes and How to Fix Them

Most learners struggle with these three skills because they do them wrong-or don’t do them at all.

Mistake 1: Reading every word slowly. You think you’re being careful. You’re just wasting time. Fix it by timing yourself. Give yourself 1 minute to skim a page. It feels weird at first, but your brain adapts.

Mistake 2: Skipping inference because it feels hard. You wait for the answer to be written out. But real language doesn’t work that way. Fix it by practicing with short stories. Read a paragraph, then write down one thing the author didn’t say but you know is true.

Mistake 3: Scanning without knowing what you’re looking for. You flip through a text hoping something will jump out. It won’t. Fix it by writing down your question before you start. “What’s the main cause?” “When did this happen?” “Who is responsible?”

One student kept failing reading sections on the IELTS. She read every word, took 10 minutes per passage, and still missed inference questions. After 3 weeks of practicing skimming, scanning, and inference for 15 minutes a day, her score jumped from 6.5 to 8.0. She didn’t learn more vocabulary. She learned how to read smarter.

Practice Exercises to Build These Skills

You don’t need fancy tools. Just use what you already read.

Exercise 1: Skimming Drill

Pick a news article. Set a timer for 60 seconds. Skim it. Then write down: What’s the main topic? One key fact. One person or group involved. You’ll be surprised how much you pick up.

Exercise 2: Scanning Challenge

Open a textbook or article. Write down 5 questions you might be asked about it: “What year?” “What percentage?” “Which country?” Now scan for the answers. Time yourself. Try to beat your time each round.

Exercise 3: Inference Journal

Every day, read one short paragraph (a tweet, a dialogue, a paragraph from a novel). Write: What’s said? What’s implied? Write down your reasoning. After a week, you’ll start seeing hidden meanings everywhere.

Try this with a restaurant menu. “Grilled salmon with lemon herb butter.” What does that imply? It’s fresh. It’s probably expensive. It’s meant to be elegant. You didn’t need someone to tell you that. You inferred it.

Why This Matters Beyond the Classroom

These skills aren’t just for tests. They’re for life.

At work, you need to skim emails to decide what to reply to. You scan reports for deadlines. You infer your boss’s real concern when they say “We should talk about the project” but don’t say what’s wrong.

When traveling, you skim signs in a foreign language. You scan for “exit” or “bathroom.” You infer why people are rushing based on body language and tone.

Reading isn’t about how many words you know. It’s about how well you use what you know. The best readers aren’t the ones who understand every word. They’re the ones who know what to ignore, where to look, and how to read between the lines.

Start small. Pick one skill. Practice it for 5 minutes a day. In a month, you’ll read faster, understand deeper, and feel less overwhelmed by text. That’s the real win.

What’s the difference between skimming and scanning?

Skimming is for getting the general idea-reading quickly to understand the main topic. Scanning is for finding specific details-like a date, name, or number-by moving your eyes fast across the text. Skimming answers “What’s this about?” Scanning answers “Where is this detail?”

Can you use inference in any language?

Yes. Inference works the same in every language because it’s based on context, tone, and human behavior-not grammar. If someone says, “I’m fine,” with a sigh and looks away, you infer they’re not fine, no matter the language. It’s about reading cues, not words.

How long does it take to get good at these strategies?

You’ll notice improvement in just a few days if you practice daily. Skimming and scanning feel natural after 3-5 sessions. Inference takes longer because it’s thinking-based-usually 2-3 weeks of regular practice. The key is consistency, not speed.

Do I need to know all the vocabulary to use inference?

No. You only need enough words to understand the context. For example, if you see “The room was silent. Everyone stared at the door,” you don’t need to know what “stared” means exactly-you know something tense is happening. Inference lets you understand meaning even when you don’t know every word.

Are these strategies only for non-native speakers?

No. Native speakers use them too. In fact, college students, lawyers, doctors, and scientists rely on skimming, scanning, and inference to handle huge amounts of reading every day. These aren’t language learner hacks-they’re efficient reading habits everyone should use.

What to Do Next

Start tomorrow. Pick one article-any article-and try just one strategy. Skim it in 60 seconds. Then scan for one detail. Then write down one thing you inferred. That’s it. No extra time. No pressure.

Track your progress. Notice how often you feel less confused when reading. Notice how you stop rereading the same paragraph five times. That’s your brain learning to read smarter.

These skills don’t make you a better reader because you know more words. They make you a better reader because you know how to use what you already know.

Scott Perlman

October 30, 2025 AT 01:51Just tried skimming a news article for 60 seconds and actually got the main point. No joke, my brain felt lighter.

mark nine

November 1, 2025 AT 01:28Scanning saved my ass during finals last semester. Found all the answers faster than my roommate could say 'wait let me read that again'. Game changer.

Lissa Veldhuis

November 2, 2025 AT 20:32People still think reading every word is smart? Lol. I used to do that until I realized I was memorizing paragraphs and forgetting the plot. Inference is where the magic happens. You don't need to know every word to know someone's lying through their teeth. That's not language that's human

Addison Smart

November 4, 2025 AT 05:05I’ve taught this to international students in three countries and it’s wild how universally it works. In Japan, they’re taught to read everything carefully. In Brazil, they rush through and miss the tone. But once they get skimming + inference? Suddenly they’re not just reading-they’re understanding culture. One student from Nigeria told me she finally got why her American boss kept saying ‘Let’s circle back’ instead of just saying ‘Fix this.’ That’s inference. That’s life.

It’s not about speed. It’s about attention. You’re not trying to consume text-you’re trying to extract meaning. And that’s a skill that translates to job interviews, dating, negotiating rent, reading your partner’s silence. I’ve seen people go from drowning in articles to leading meetings because they learned to read between the lines. You don’t need a PhD. You need curiosity and five minutes a day.

And no, you don’t need to know every word. I read a medical journal last week with half the terms I didn’t know. But I knew the conclusion because the structure screamed it. Headings. Contrasts. Repetition. That’s the language of logic. Your brain already speaks it. You just forgot you knew how.

Try this: next time you’re stuck on a long email, don’t read it. Skim the first line of each paragraph. Then scan for the word ‘action’ or ‘deadline.’ Then ask yourself-what’s the emotional subtext? Is this urgent? Is this a complaint? Is this a favor disguised as a request? That’s not reading. That’s reading between the lines. And it’s the most powerful skill you’ll ever learn that no one teaches you in school.

Eva Monhaut

November 5, 2025 AT 00:52I used to think inference was for literature majors. Then I started reading my mom’s texts. ‘I’m fine’ with three periods? Yeah. She’s mad. Not because of grammar. Because of silence. Same thing happens in work emails. ‘We should talk’ followed by a pause? That’s not a suggestion. That’s a warning. I started applying this to everything-social media, ads, even my dog’s body language. Turns out, humans are terrible at saying what they mean. But we’re amazing at hiding it. And if you learn to read the gaps? You stop being surprised by everything.

My brother still reads every word of his work reports. He spends hours. I skim, scan, infer. I’m done in ten minutes. He thinks I’m lazy. I think he’s wasting his brain on noise.

Sandi Johnson

November 5, 2025 AT 18:10Oh wow so you're telling me I don't have to read the entire 50-page PDF? What a relief. I thought I was just bad at reading. Turns out I was just being a sucker for words.

Michael Jones

November 7, 2025 AT 09:56These aren’t strategies they’re survival tools. We live in an age where attention is the only currency that matters. The people who win aren’t the ones who read the most. They’re the ones who read the least-intentionally. Skimming is mindfulness for the mind. Scanning is focus under pressure. Inference is intuition trained by logic. This isn’t about reading faster. It’s about thinking clearer. When you stop trying to absorb everything you start seeing patterns. And patterns are where truth hides. The real question isn’t how to read better. It’s how to stop letting the world drown you in noise. These tools don’t help you read. They help you choose what to listen to.

Ronnie Kaye

November 7, 2025 AT 22:59Bro I tried this on my Tinder matches. Skim their bios. Scan for ‘dog person’ or ‘travel junkie.’ Inference? If they say ‘I love spontaneous adventures’ but their pics are all at Starbucks? They’re lying. And I’m not even dating anymore. Just collecting data. This stuff works everywhere.

Rakesh Kumar

November 9, 2025 AT 11:12In India we’re taught to memorize everything. I failed my GRE because I read every line like it was scripture. Then I learned to skim and scan. I found my answers in 30 seconds. I didn’t need to know every word. I needed to know where to look. Now I teach this to my cousins. They think I’m a wizard. I’m just not wasting time on noise anymore.

Bill Castanier

November 10, 2025 AT 13:22Best advice I ever got. Stop reading. Start hunting.

Priyank Panchal

November 11, 2025 AT 22:50You think this is new? We’ve been doing this in Indian universities for decades. But you Westerners act like it’s some breakthrough. We call it ‘smart reading.’ You call it ‘life hack.’ Same thing. Just don’t pretend you invented it.

David Smith

November 13, 2025 AT 08:31Of course this works. People who can’t read properly just need to be told to stop being lazy. I’ve been doing this since high school. I read the first sentence of each paragraph and the last line of the conclusion. That’s it. The rest is filler. You’re not reading-you’re digesting. And if you can’t do that? Maybe you shouldn’t be reading at all.

Tony Smith

November 13, 2025 AT 10:32While I appreciate the practical utility of these methodologies, I must respectfully contend that their efficacy is contingent upon the reader’s foundational literacy proficiency. One cannot effectively skim a text without possessing a lexicon sufficient to discern semantic salience. Furthermore, the cognitive act of inference presupposes a robust internal model of pragmatic context-a capacity that is neither universally distributed nor easily cultivated. Thus, while these strategies may serve as useful heuristics for the moderately literate, they risk becoming epistemological shortcuts for those lacking the requisite linguistic scaffolding. One might argue that true comprehension requires immersion-not efficiency.